The Tanimbar-island Python

(Morelia nauta; Harvey, Barker, Ammerman & Chippendale, 2000)

General and Reproductive Husbandry

Written by Balázs Roland Ferencz, published in ELAPHE (DGHT) in August, 2005

Pythons from the Indo-Australian region tend to have a lot of variants in colour and size on the different islands. Moreover, as a consequence of the isolation, sometimes new species and subspecies evolve.

This phenomenon can be observed in the case of the Amethystine pythons as well. The taxonomic confusion between the two former subspecies (Morelia amethistina amethistina, Morelia amethistina kinghorni) and among the hues was cleared by the results of Harvey, Barker, Ammerman and Chippendale (2000). In their researches they described five independent species: the medium-sized Amethystine python (Morelia amethistina) living in Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, the large Scrub python (Morelia kinghorni) from the northern parts of Australia, the Morelia clastolepis also known as the Molukka python, the python from the Halmahera-islands (Morelia tracyei) and at last but not least the dwarf variety Tanimbar python (Morelia nauta), about which the present article is about.

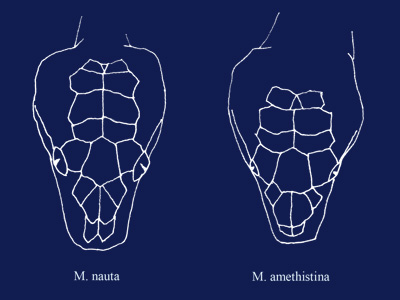

The Morelia nauta can easily be distinguished from its ancestor, the Morelia amethistina not only by the basic morfological differences detailed below, but also by the scalation of the head. Besides the smaller differences, the difference on the parietalia is the most striking. While both parietalia of the Amethystine python have two, that of the Morelia nauta have four parts. As the snakes' having big head-scales is an atavistic feature, this characteristic of the Morelia nauta proves that this species developed later, as the consequence of the isolation, than the Morelia amethistina.

Distribution and habitat

Tanimbar-islands are situated in Indonesia, in a region called Banda and bordered by Timor, Ambon and Irian Jaya. Tanimbar consists of a main island called Yamdena and several smaller islands surrounding it. The vegetation of the island is made up of tropical rain forests. The bush-, and tree-strata of these forests are inhabited by the Tanimbar pythons.

Build and colour

In fact, on the islands the Tanimbar python plays the ecological role of the Green tree python (Morelia viridis) spread all around the area. According to this, its physique has been adapted to an arboreal lifestyle.

Morelia nautas grow much smaller than their relatives. The average size of an adult is between 1,5-2 meters, which mainly consist of the elongated neck and the tail specialised for clinging. Although its body is slender because of the loss of weight, it is not as flat as that of the members of the Corallus family, for example. Its head is big and is strongly separated from the neck, its teeth are long. These characteristics ensure the holding of the prey for animals hunting in the foliage.

The big eyes and the heat-sensitive thermoreceptive labial pits refer to a night lifestyle. Its eyesight seems to be much better compared to other boids.

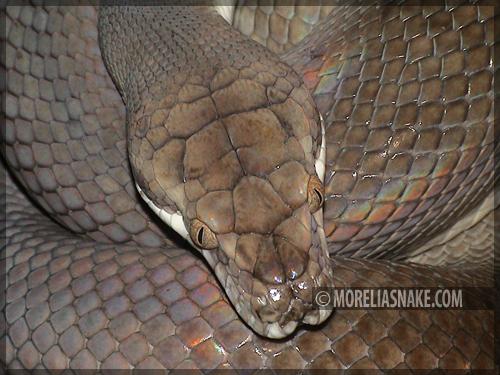

Although its colour has been changed a lot compared to the Amethystine python, the traces of the dark strip from the temple to the nose and of the striking light part next to the lip, which characterise the ancestors, can be seen on the adult Morelia nauta, too. The most common colour is patternless silver, which can range from light silver to graphite tending to black. It is the most typical of the silver ones that where the sun meets their skin more intensively, light is reflected as taken to its components. This iridescence is especially remarkable at the darker snakes.

The gold ones have a brownish base, but where it faces the sun it may seem to be yellowish. This colour can the best be compared to the Indonesian variant of the Leiopython albertisii. Rarely both variants have so called spotted specimens, whose bodies have white spots scattered unsystematically or longitudinal short bands.

Each specimen has a white belly, while at the edge of the caudal some light strips may appear.

Behaviour

In contrast to other, hot-tempered Morelia-species, the nauta is a quite tame, sometimes rather timid animal. Even if scared, it almost never bites, but it escapes instead, and as soon as possible it hides itself. When caught, it passes stinking secretion, as the arboreal boids typically do.

They do not live a night life as strictly as other pythons do. They often move during the day, too, what makes their feeding easier, and, moreover, their actual behaviour can be studied more thoroughly.

Habituating to the terrarium

Tanimbar pythons come almost exclusively from their habitat and were caught in the wild. As they are sensitive animals, I think it is worth sharing my experiences with those keeping such an animal.

Most animals arriving to Europe are infected with parasites inside and outside alike. Each of my animals had 20-30 ticks on their skin. Because of this and to prevent the possible miting, I treated my snakes and the terrariums with chemicals containing fipronil. The parasitological analysis of the faecal revealed the presence of ova of different intestinal worms carried by rodents. I treated this with dosing Ivermectin injections. At the stock of a breeder colleague of mine, several specimens which had been in captivity for half a year died spontaneously, while during this time took the food without any trouble. At each case a lot of eelworms were found at the tissue of the lungs.

The male of 100 cm and the female of 140 cm were placed temporarily into a terrarium of 80x70x70 cm which was equipped -with branches and artificial plants- especially for arboreal snakes and contained a lot of hiding-places. I ensured constantly high temperature (28-32 C°) and high humidity. The snakes spent their first two or three weeks with lying continuously in the water, what only rarely happens to them. It caused anxiety that I saw the animals drinking several times a day. The unusually high water absorption can be the symptom of desiccation or, as a consequence of this, of renal insufficiency. Animals coming from Asia or Indonesia are not provided with sufficient water either during the transport or on the farms, which can be very dangerous in the case of an arboreal animal that consumes dew daily. The animals are often without symptoms for weeks or months. But the renal insufficiency developed during this period cannot be cured after a certain time.

My animals got better after a while. Although the male took the food normally, there were some problems with the female. Probably as quarantining it into the hygienic but tight plastic box, a lentil-sized piece was missing from her nose. I treated the injury with a chemical containing iodine. But when she was shedding, the wound renewed and was only healing slowly. As I could see, it was painful for the animal. She refused all kinds of food, and, moreover, after a while the presence of the rodents caused gradually growing stress. As a consequence, even after the wound was healed, the animal reacted aggressively with huffing to my feeding attempts. At last, it was revealed that the only thing she could not resist was the new-born, still mucous and bloody, rat given her at night. It took two months to habituate her from this very poor nourishment to consume already-killed food animals.

Preparing the living-place

When preparing the terrarium we have to take into consideration that we talk about an arboreal species, so it should be at least 60-70 cm high. I keep my animals in a terrarium of 120x70x80 cm. When I separate the male for certain periods, I put him into a terrarium of 80x70x90 cm. The material of the cage is olive-green, wooden lamina. The darker background and the proper height increase the animals feeling of security. (The joining points should be covered by silicon or plastic.)

In the terrarium there are shelves of different height, where I sticked flowerpots as hiding-places. There are some artificial plants giving shade, branches and roots, too. The temperature is 28-32°C during the day, and it is better if it does not go below 25-26°C at nights. The high temperature is ensured by a simple flex-bulb and a ceramic heater connected to a thermostat. The heating facilities are at one side of the terrarium, so the other side remains unheated, and this can mean a 6-7°C difference between the two sides. The animals can choose between a warmer, "sunny" and a calmer, shaded place.

The species requires constantly high humidity. We should spray the animals with lukewarm water more than once a day. If the terrarium is too dry, the animal may have problems with shedding, and respiratory infections or dyspepsia (constipation, regurgitation) may occur.

For the ground I mix black mould and peat in equal proportion. This mixture retains water well. If loosened weekly, it preserves its proper condition for long. The snakes may spend more days at their favourite hiding-places, so we should pay attention to keep the ground of these places dry in order to prevent the rotting of the caudal. Living-places equipped with natural materials should be treated with chemicals -containing fipronil for example - to prevent miting. Ventilation is ensured only by a tight wire netting consisting one third of the cover. Among the branches I placed some water-bowls in which I change water two or three times a week -after feeding I necessarily do so, as snakes do not like stale water. Some bigger bowls serve as "baths". Boas normally like baths which are just appropriate for their body as they do not like floating. Make sure that the animals' water remain lukewarm.

Feeding

In the wild Morelia nautas -as their teeth suggest -may capture birds as well as smaller mammals, but in captivity you had better feed them with rodents.

Tanimbar pythons habituated to terrarium are not faddy, so can be fed with any kinds of clear, not too fat and constantly available mouse or rat. We should pay attention not to overfeed the males. I feed my female animal (2m) with two or three rats of 150-170g, while the male (1,7m) gets either only two or three full-grown mice, or one or two rats of 50g. I feed them in every 10-14 days.

For many reasons, it is more practical to feed the animals with already-killed rodents. Arboreal snakes swallow very clumsily on the ground, their mouths may be filled with peat, for instance. When feeding, they should be made strike from a perch.

"History" of the species-breeding

When I wrote this article in 2005, the history was the following: Being a new species, Morelia nauta has just become popular among the collectors. As they are quite sensitive, so far they have been bred in captivity only few times. Each clutch has contained only few eggs, and, in addition, Morelia nautas' hatching proportion in captivity has been registered as very low in general.

It is supposed that, according to a research made on the Internet with the help of Nick Mutton, up to 2004 the species could be made copulate at four places. First, it was successful at V.P.I. (Vida Preciosa Institute) lead by David Barker. Only here could they have an F2 generation. At Nick Mutton's, four animals hatched from eight eggs, and at a Canadian breeder one baby was born. According to Nick Mutton, 25 specimens have been born on the American continent.

One progeny is known in Europe. At the webpage of Corinne Harwick, there has recently been published a photo-series about nine hatching nautas. The event happened in 2002.

Sex determination

There are certain morfological differences between Morelia nauta males and females. Males are more slender, their heads are smaller, not so wide at the back, and their tails are longer than that of the females'. Anal spurs are quite developed at both sexes, as generally in the case of arboreal species.

The most reliable method of sex determination is probing done properly. The probe does not pass either at all or not deeper than 2-3 sudcaudal scales in the females, while in the males it can pass to a depth of 8-12 subcaudal scales.

Copulation

The climate in the Tanimbar region is steady all over the year according to the meteorological data. Both temperature and humidity are high. The only change is the small or medium decrease in rainfall in the autumn months.

I tried manipulating my animals in several ways. As the consequence of their cooling -which is a typical method at pythons-, my snakes caught a bit cold. I could only make them copulate by suddenly but not drastically decreasing humidity-level while increasing temperature and light at the same time.

The animals I have owned since 2001 autumn copulated first in March 2002. Copulations were repeated for two days. The female slowly started to fatten and refused food. Two months later, she lost weight almost overnight and began to eat again. This phenomenon was described by other breeders, too. It's more likely that these snakes torn away from nature do not regenerate as quickly as it seems from outside. Their bodies, by the sudden absorption of the ova, save them from an exhaustion that might be fatal.

I placed my animals into a common terrarium with the above mentioned climatic manipulation in 2003 autumn. I increased the effects by using UV irradiation of small intensity for 2-3 hours, two or three times a week. The daily copulation after the short period of courting (exciting by anal spurs) lasted from 23 October to 30 November. The male did not take food until January. The female did not eat after the first some copulation for two weeks, but afterwards she became very greedy. I fed the animal intensively until January. The posterior third of the animal's body started to fatten quickly. During gravidity, her colour changed to black.

The female did not eat anything in January, and stayed at the shady, protected side of the terrarium. She shedded in February, and since then she was constantly lying under the lamp where the temperature was high, 34-38^(o)C. Seeing this, I placed in several "hatching-boxes" for her, and in 1-2 hours she occupied the one on the warmest place. These were nesting boxes of 25x25x25cm with an entrance of 10 cm in diameter. I filled the box half with mould, peat and moistened vermiculite in equal proportion. I sprinkled the ground in every two days and loosened it with a stick regularly. At this time the female was huffing heavily even for the smallest insult. The male had to be taken out when placing in the box, as he also likes staying at the hiding-places and this would bother the already nervous female.

On 20th February the female was lying on her back, in an inverted position. She started laying eggs at 7-8 am on 26th February. At 6 pm I, with a help, took the female off the eggs that she protected with bites.

The period of gravidity is regarded to be long even in the Amethystine group. The period of holding the eggs is normally between 50-80 days at most Morelia species.

The clutch contained 20 eggs, out of which 3 were infertile. Each egg was 50-60 mm long and 30-35 mm in diameter. The eggs were cleared from the soil-pieces with an easel, then half-dug into the hatching area were placed into an incubator. The female separated one egg from the others, which in the end turned out to be good and a healthy baby hatched from it.

The hatching box can not be placed back to the terrarium because the female would continue hatching when smelling the eggs, and this would make her increasingly weak as she would not eat. The animal was very vexed for 2-3 days, so I covered the frontal glass of her cage. In the second week after laying the eggs she shedded, so she regained her original silver colour. After shedding she got a mouse. As the female was very weakened, I ensured her with limitless amount of food during the summer. In spite of this, it took two months that her loose, folded skin became tight again. According to this, it is likely that females are not able to breed every year.

Incubating the eggs

The incubator was a 30 mm thick, tight-fitting styrofoam box. Inside I placed a plastic box with water, and a water-heater equipped with a thermostat, which kept the temperature of the water and, through this, of the air constantly at 29^(o)C. I placed the eggs into a plastic box (Fauna box) of 33x20x20 cm above the heater. I covered the perforated top of the box with a pane (placed in sloped) so as to prevent the dropping back of water.

I used vermiculite as incubation medium. I moistened one part of vermiculite with one part of water. This mixture should be packed or foiled some days before using.

At the second week of incubation, one egg turned out to be infertile. It collapsed and started to get mildewing. I removed most of the mildew with paper when controlling in every 4-5 days in order to stop it from spreading to the healthy eggs.

From mid April on, the eggs seemed to dehydrate as the sign of the coming hatching. This process created slits among the eggs sticked, so the babies could find their ways out even of eggs in the middle or at the bottom of the clutch.

The hatching started on 5th May and was finished by the next evening. The process was unusually quick. Babies were born from all the 16 eggs.

Rearing the offspring

The baby nautas seemed to be very vital compared to other neonatal morelias. When born they were 40-45 cm long. They moved very swiftly and they bit already in the incubator.

Each baby was placed into a plastic box of 15x12x13 cm perforated from the side and the top. There were some mould with peat, a water bowl of 5 cm in diameter, two bamboo-sticks and an artificial plant in each box. The boxes were in a room of 26-29^(o)C, and I humidified them two or three times a week.

Young Morelia nautas may catch tree-frogs and geckos in the wild, while we should feed them with mouse in captivity.

The young shedded after two weeks, and they accepted fuzzy mice (of 14-17 days) given alive. They liked striking at moving mice, so we should not be afraid that they may be scared by a bigger prey. Out of the 16 offspring, two refused food, but after 14 days, they also accepted the pinky mice the eyes of which were just to open.

At the second feeding, they accepted two or three already-killed mice from pincers. Later I placed them into two terrariums of 35x40x45 cm. Here they behaved quite aggressively in contrast to the adults. After one of them ate its cagemate spontaneously, I moved them back into their boxes, and I have been keeping them individually since then.

The juveniles have a good growing force. They started to change their neonatal orange colour to the silver of the adults in the third month. All the offspring are patternless. When probing them at the age of 100 days, the tail of the females tended to be 30% thicker. They may reach their maturity at the age of 3-4.

Conclusions

Experiences prove that most of the Morelia nautas captured and brought to Europe die within half a year after put into a terrarium. The ones feeding alone may seem to be in good conditions, but their final regeneration may take one or two years. It is worth trying to breed them only after this.

Keeping them is more or less the same as keeping the Morelia viridis and Morelia spilota cheynei.

Making them breed is not easy, but the rearing of the juvenils is easier because of their vitality than that of other morelias. As juvenils tend to regard each other as preys, their rearing can only be done by separation. Adults can be put together without any problem. The species is of CITES II., and it belongs to category B in the European Union.

Timeline

2005

The copulations lasted from 26th October to the middle of December 2004. The female laid the clutch of 22 eggs on 6th February 2005 beating her record of 20 eggs of the previous year. On 17th-18th April 2005, 17 babies were born. One of them was born without eyes and it died in two months. The 16 other snakes feed without any problem.

The palate of the juvenils is either dark grey or black compared to the white and pink palate of the adults. It is worth mentioning that the juvenils in stress do not often bite but by gawping they show their strikingly coloured palates, just like other snakes do (Deudroaspis, Aq...etc.)

2006

Although this year I have been keeping the adults isolated so as to maintain the condition of the female, from December they clearly show the signs of sexual activity.

2007

25th April -18 babies

2008

17-20th April-17 babies

2010

28-30th April -16 babies

2011

19th April 5 babies

2012

06th May -7 babies

Written by Balázs Roland Ferencz

Photos by Balázs Roland Ferencz

Consultants: Nick Mutton, Tamás Sátorhelyi (vet), Gábor Kósa, Balázs Hárshágyi, Csaba Géczy.

Secondary Literature:

Barker, David G. & Barker, Tracy M., Pythons of the Word, Volume I., Australia, The Herpetocultural Library, 1994.

Ross, Richard A. & Marzec, Gerald, The Reproductive Husbandry of Pythons and Boas, The Institute for Herpetological Research, Standford, California, 1990.

Michael B. Harvey, David G. Barker, Loren Ammerman, and Paul Chippendale. 2000. Systematics of pythons of the Morelia amethistina complex (Serpentes: Boidae) with the description of three new species. Herpetological Monographs 14: 139-185.

www.inlandreptile.com