Care and Breeding of the Amethystine Python

(Morelia amethystina, Harvey et al, 2000)

Written by Balázs Roland Ferencz

The Amethystine python complex was divided into the following five species by Harvey, Barker, Ammerman and Chippendale in 2000: the Seram python (Morelia clastolepis), the Halmahera python (Morelia tracyei), the dwarf Tanimbar python (Morelia nauta), the former subspecies, the high-grown Scrub python (Morelia kinghorni) from Australia, and the Amethystine python (Morelia amethystina) living in Indonesia and Papua New Guinea.

Description

The older herpetological literature often speaks about high-grown Amethystine pythons. Worrell (1963) is said to see a dead amethystine python of 860 cm. But experts are more ready to believe the reports of Kinghorn (1967), Dean (1954) and Gow (1989) describing specimens of 670-760 cm. The largest captive specimen was 500 cm long (Barker, 1994). But these reports were all about animals captured in Australia, so the information refers to the Morelia kinghorni. But the Amethystine, which is more often brought in Europe, grows much smaller. Adult females are 250-350 cm, while males are 180-250 cm long. A smaller male's body is slimmer than the wrist of an adult man.

Their build may remind us of the representatives of the genus Corallus, but their bodies attain sufficient bulk rather than to be laterally compressed. The elongated tail and the neck give the half of their body. The slender body is very strong-built. Their scales, especially on the belly, are large. These characteristics refer to their arboreal lifestyle. The head is big and is strongly separated from the neck. Their eyes are big and bulging, and they have fine thermo-receptive labial pits which help them in the orientation at night. Their teeth are the biggest among pythons, and may help them to capture birds.

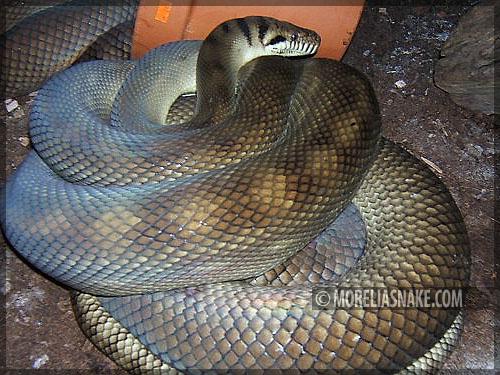

Due to the isolation, these snakes are varied in colour. From the reddish-orange specimens of the highlands of the Wamena area to the zigzag striped animals of the Merauke island, many variations exist. I myself keep snakes from the Sorong peninsula connected to Irian Jaya. It is called the "Sorong bar neck" in certain publications. The colour of this morph is quite difficult to describe. The adults are olive-green, sometimes greyish or dark yellow. Each scale is darkly contoured. The thickness of this may vary with the parts of the body, so there are lighter and darker parts, too. At certain specimens these smudges may add up the ringed tail. At others there are more pale parts. This colour imitates the visual effects of the sunshine coming through the foliage. The belly is white or off yellow. On the neck there are two wide bars and some more black smudges, that is why it is called the "bar necked".

There is a black stripe passing from the eyes to the labials. The large scales on the top of the head are bordered with dark pigment, so they seem to stand out of the skull. The labial thermo receptors are black and white patterned, and this makes us believe that the teeth of the animal are standing out of the mouth. To sum up, the amethystine has one of the most striking facial look among the pythons. In sunlight its skin is iridescent, its official name was given after this.

Diffusion and habitat

This species can be found on most islands of Indonesia and Papua New Guinea. It lives in tropical rain forests, scrubs and coastal areas of rich vegetation.

The amethystine pythons are active during the night. The young live an arboreal, while the adults of more than 1.5-2 meters live a partly arboreal lifestyle.

Behaviour

The amethystine pythons, just like the Morelia and Liasis species spread in the region, are not very friendly animals. But this habit can be broken easily. Before reaching into the terrarium, we should kindly touch the nose of the animal with any longer object (like a stick or forceps). This will make the animal recoil. (But never do this when feeding!) If this rite is regularly repeated from its infancy, the animal will learn when it can approach. It will not associate the opening of the terrarium with feeding, so we can avoid a lot of bites. (Similar methods are used with other captive animals, too.)

If we have to catch it, we should start taking by the back of the neck. It will cover us with foul discharge, like other snakes do, too. The shocked animal may seize the hand keeping its head, so it is better if we have a help there. The only dangerous situation is the feeding. These snakes are able to keep their elongated bodies in horizontal position while clinging only with their tails. So the animal, excited by the smell of the prey, can attack its victim from a long distance. But just because of the long distance, it may miss the target and bite something else that is moving, our hand, for example. Although they are not able to cause great harm, their bites are quite unpleasant, so we should pay attention and offer the food with long forceps. Moreover, it is better if we keep the animals separated.

The amethystine pythons are not as large and dangerous as they are often said to be, but their care is not always easy. I recommend it only to experienced breeders.

Habituating to the terrarium

I acquired my own specimens from Indonesia between 1999 and 2001. Then they were 70-120 cm long and six month-one year old. After their arrival to Europe, they were treated with chemicals including fipronil against mites (acarina). Later on they were given an inermecin injection to get rid of inner parasites.

The animals were placed to a common terrarium of 70x60x80, but later they turned out to feed and develop better if kept separately in quite narrow cages of 35x40x50.

All of them accepted the dead mouse put in for the night. Later on, they took this food from forceps, too. There was one problematic specimen which kept on refusing rats, so it ate only mice until the age of 5 and the length of 3 meters. Then its taste changed and now it is ready to accept rats of appropriate size.

At the beginning we should pay attention to the water supply of the animals, because it is often neglected on wild farms and especially during transport. Wild captured animals are often close to dehydration, and this may cause serious renal damage. Their water should not be too cold. We should change it several times a week if possible, because most snakes are sensible to the quality of drinking water, and if it is stale they are not willing to drink it. We should put some water-bowls between the branches, because younger specimens are not ready to climb down to the ground, and they do not drink, at least not as much as their organisation may claim.

Cage maintenance

The specimens longer than 1.5 meter should be placed to their final cages. I keep the adults in a terrarium of 150x70x80. For the ground I mix black mould and peat in equal proportion. It stays crumbly but does not stick and retains water well. I put branches and artificial plants in the terrarium. My animals have water-bowls which may serve as baths, but the bowls should not be too wide as they do not like floating but prefer baths which are just appropriate for their bodies, so they can feel more secure. If hiding places are ensured, the animals become more relaxed and less ready to bite, so they will be easier to deal with. Make sure that the ground of the rest-, and hiding places remains dry!

Air-conditioning

The appropriate temperature is ensured by a simple flex-bulb and a ceramic heater connected to a thermostat. The heating facilities should be outside, on one side of the ventilating bars on the roof. We should choose bulbs which ensure 28-32°C in the middle of the terrarium, and at least 22-24°C at night. So the animals can choose between warmer, "sunny" and calmer, shaded places.

The amethystine pythons require constantly high humidity. We should spray the terrarium with lukewarm water more than once a day and keep a part of the ground (not where the animals tend to rest) wet. Exposure to too low temperature and humidity may cause respiratory infections, problems with sloughing or indigestion.

Feeding

In the wild the amethystine pythons feed on smaller mammals and birds, while we can feed them with constantly available mice and rats in captivity. The adult males are given one or two, while females two to four rats every time. I feed them in every 15 days, with already killed rodents. This is a more considerate and practical method compared to giving live animals.

The satisfied animals drink several times and a lot. The amethystine pythons are very greedy, make sure the males are not overweight!

Nutritional supplements like vitamins should not be given to the animals, as this may lead to overdosing of certain vitamins in the case of animals feeding on whole rodents.

Sex determination

Sexual dimorphism is apparent in adult amethystine pythons. Males are with 30% shorter than females, their bodies are slender, their heads are smaller and thinner.

The most accurate method of sex determination is probing. The probe passes to a depth of 3-4 subcaudal scales in a female, while to 10-14 in a male.

Breeding

The first reports about the species breeding are quite ancient. Successful hatchings are told by Boos in 1979, by Charles in 1985, by Wheeler and Grow in 1989 (Ross and Marzec, Barker and Barker). However, the amethystine python is not frequently bred in captivity. Specimens born in captivity can rarely be seen at European fairs.

My breeding stock consists of a male of 190 cm, and two females of 300 (hereinafter "A") and 350 (hereinafter "B") cm. The male showed sexual activity first in December 2004. He copulated with both females. The female called "A" must have been to young, as she laid 12 big (of 7 diameter) but infertile eggs on 7th February 2005. The female called "B" laid 24 eggs on 22nd April 2005. This was probably a record according to the data found in the literature. (According to Barker, the biggest clutch contained 21 eggs.) Unfortunately, during the snake's laying eggs, I was staying in another town, so I could take these eggs from the female only three days later. The eggs which were put under warming lamps lost so much water that they could not regenerate in the incubator. At the end of the incubation, only four little snakes hatched, but they were healthy and fed normally. All the other eggs contained died embryos, so they were fertile.

However, it was the year 2006 that gave the real breeding results. From 2005 on, I manipulated my animals by increasing the intensity of light and the temperature of the cage, while decreasing humidity. As a result, after a short courting the male copulated with female "A". Female "B" was refusing him, she was almost escaping from him.

Female "A" was feeding intensively after the copulation. Later on she gave up eating, the last third of her body became thick, and she often sunbathed. The female's colour changes during gravidity. The gravid amethystine becomes dark grey. After her shedding of 10th April, I placed in a hatching box in which she moved immediately and she started protecting it. The hatching box was a nesting box of 30x30x30 filled with peat. We should pay attention that the thickened part of the animal's body can enter the box. The female was often moving from the sunny area to the nest. She laid the eggs on 7th May. By then she normally becomes quite weak, so she can be fed more intensively than usual for some months.

Incubating

With a help, I removed the clutch of 21 eggs from the female, and after cleaning them with an easel I put them into an incubator. The clutch contained three infertile eggs, so called "slugs", which were removed. The incubator was a 4 cm thick styrofoam box . There was some water at the bottom, and a water heater equipped with a thermostat ensured the appropriate temperature. The eggs were placed on wet vermiculit (1 vermiculit : 1 water) into a plastic box of 30x22x20. It was 29-31°C and 90% humidity in the incubator. In the first two months of the incubation two eggs discoloured, but the rest remained white. From 4th July on, the eggs seemed to dehydrate which was the sign of the coming hatching. On 1st and 2nd August, 16 babies hatched.

Rearing the offsprings

The neonate amethystine pythons were 60-67 cm long. The first sloughing happens quite late compared to other pythons, only at the age of 1-2 month, and the animals often start feeding before. The just shedded snakes are dark red or orange, and their characteristic collars can already be seen.

I keep the young snakes individually in 26-28°C in small boxes equipped with water-bowls and with sticks to sit on. Their cages should be humid and clean.

Their feeding is easy. They are usually ready to accept fuzzies. Later on, when they are not so scared they can be fed with forceps, too. I suggest keeping the animals individually. The juveniles have good growing force.

Their colour gradually changes into grey, and the adulthood patter appears. By the age of 1.5-2, their final colour of olive green appears.

The young are quite helpless, but the ones of nearly 2 meters are aware of their force. We should be careful when dealing with them, otherwise they may bite us.

They become sexually mature at the age of 3, but they should not be bred before the age of 4.

The species is declared to be endangered, and of category II of the Washington treaty (CITES), and of category B in the European Union.

Written by Balázs Roland Ferencz

Photos by Balázs Roland Ferencz

Secondary Literature:

Ross, Richard A.; Marzec, Gerard, The Reproductive Husbandry of Pythons and Boas, IHR, Stanford, California, 1990.

Barker, David G.; Barker, Tracy M., Pythons of the World, Volume 1, Australia, The Herpetocultural Library, 1994.

Ferencz, Balázs Roland, Terrarienhaltung und Vermehrung des Tanimbar Pythons (Morelia nauta, Harvey et al, 2000), Elaphe (DGHT) 20 August, 2005.

Ferencz, Balázs Roland, The Tanimbar island Python, Moreliasnake.com, 2005.